Introduction

Quantum computing hardware must operate under extraordinarily controlled conditions to preserve fragile quantum states. Even slight environmental disturbances – thermal fluctuations, mechanical vibrations, electromagnetic noise, or gravitational forces – can induce decoherence, causing qubits to lose information[1]. This article investigates the hypothesis that combining microgravity with ultracold (near-absolute-zero) temperatures creates an environment closer to “ideal” for quantum computation, one that mitigates not only gravity-related issues but a broad spectrum of noise and error sources. In essence, the extreme conditions of space (microgravity and cryogenic vacuum) are argued to improve qubit coherence times, suppress decoherence mechanisms, reduce gate and readout error rates, and enhance overall quantum computer performance beyond what is achievable in terrestrial labs.

We develop this argument through theoretical reasoning and examination of emerging experimental evidence. On the theoretical side, gravity’s influence on quantum systems can be seen as a source of dephasing – for example, spatially separated qubits accumulate relative phase via gravitational redshift, acting like a “noise channel”[2]. By eliminating weight and gravitational potential gradients, a microgravity environment may essentially remove this subtle decoherence channel. Moreover, operating at near 0 K drastically suppresses thermal noise and blackbody radiation that would otherwise perturb qubits. Together, these conditions emulate an ideal isolated quantum system. We survey how four leading qubit platforms – superconducting circuits, trapped ions, ultracold neutral atoms, and photonic qubits – stand to benefit. We then review evidence from space-based quantum experiments (e.g. on the International Space Station), drop-tower microgravity tests, and temperature-dependent studies that support the performance gains in these extreme environments. Finally, we propose an experimental design to directly test the hypothesis by comparing identical quantum processors in ground versus microgravity conditions, with careful isolation of gravitational effects from other factors.

Microgravity and Cryogenic Conditions as Ideal Qubit Environments

Operating in microgravity (essentially free-fall) provides a uniquely quiescent environment where many perturbations present on Earth are minimized. In a weightless setting, there is no “up” or “down” pulling on equipment or particles; experimental apparatus can be more symmetrically designed and free of sagging or stress. For quantum devices, this means support structures and alignments remain more stable over time, potentially reducing slow drifts and vibrations that would miscalibrate qubits. For example, cold atom traps on Earth must constantly fight gravity to hold atoms, which requires steep trapping potentials and introduces asymmetry; in microgravity, the same atoms can float freely or be confined by much gentler, symmetric forces[3][4]. This eliminates one significant source of decoherence (the need for strong fields that can perturb quantum states) and allows atoms or ions to remain in place without levitation-induced noise. From a cryogenic perspective, near-absolute-zero temperatures freeze out almost all thermal excitations in the environment. Qubits at millikelvin temperatures are far less disturbed by thermal photons or phonons, and residual gas in the vacuum chamber condenses on cold surfaces, yielding an ultra-high vacuum with collision rates nearly zero[5]. Combined, microgravity and ultracold vacuum approximate an ideal isolated system: no convective air currents, negligible mechanical stress, minimal electromagnetic interference, and extremely low gas collision or blackbody disturbance. In such an environment, qubits can maintain superposition and entanglement significantly longer, improving their coherence lifetimes and fidelity of operations.

Beyond intuitive arguments, recent studies have formalized gravity’s role as a decohering influence on quantum hardware. For instance, one analysis treated gravity as a pervasive dephasing field: in a static 1g field, entangled qubits experience slight phase shifts due to gravitational potential differences, accumulating as a systematic decoherence over time[2]. Eliminating gravity (i.e. in free-fall) would remove this phase drift, unifying the proper time experienced by all qubits and thereby preserving relative phase coherence. In other words, microgravity can halt a “universal dephasing channel” that affects all quantum platforms[2]. Likewise, models of gravitational time dilation predict that a quantum superposition of an object at two heights will lose coherence as the internal clocks tick at different rates[6]. Only by placing the entire system in the same gravitational frame (free-fall orbit or deep space) can one avoid such relativistic decoherence. These theoretical considerations strengthen the notion that gravity – even static Earth gravity – is more than just a trivial experimental inconvenience; it subtly but inevitably leaks information from quantum states into the gravitational field, unless we can remove or homogenize it. Microgravity thus offers a route to “turn off” one more source of qubit-environment entanglement.

Crucially, microgravity’s benefits are intertwined with maintaining a cryogenic, vibration-free setting. Space is often thought of as cold and quiet, but it is not automatically so – the cosmic microwave background is 2.7 K (and Earth orbit ~4 K)[7], and spacecraft are subject to solar heating and internal vibrational noise from pumps or fans. Reaching the ~10 mK regime needed for superconducting qubits still requires active refrigeration even in space[7]. Fortunately, space platforms can be equipped with closed-cycle cryocoolers or cryogen boil-off systems to achieve comparable temperatures to terrestrial dilution refrigerators. These have been used on satellites for years (for example, space telescopes and particle detectors). What microgravity adds is a reduction in convective and gravity-driven effects in the cryostat: no buoyant hot spots or liquid stratification, and potentially easier alignment of multiple cooling stages without sag. In the weightless environment, cryogenic fluids and components can be arranged without concern for orientation, which may simplify some aspects of refrigeration engineering. More importantly, microgravity allows extreme vibration isolation techniques that are impossible on Earth. A spacecraft can be designed as a drag-free satellite – using thrusters to cancel out even minute forces – such that an experimental package literally free-floats without touching the walls. This was demonstrated by missions like LISA Pathfinder, achieving acceleration noise below 10^−14 g. In such a drag-free, 0 g environment, mechanical disturbances are vanishingly small, far below the seismic and acoustic noise floor of the quietest laboratory. For quantum computing hardware, which is highly sensitive to vibration (as discussed later), this offers an unprecedented stability of the reference frame.

In summary, microgravity and near-absolute-zero conditions together create a “silence” in all channels of decoherence: thermal, mechanical, and gravitational. We next examine in detail how specific qubit implementations stand to gain from these conditions, and what improvements have already been observed or predicted in practice.

Superconducting Qubits in Microgravity

Current Challenges: Superconducting qubits (such as transmon circuits) are typically operated at ~10–20 mK in dilution refrigerators on Earth[7]. At these temperatures, thermal excitations are suppressed and the superconducting state is stable, but qubit coherence is still limited by material defects, stray electromagnetic noise, and occasional high-energy radiation hits. Coherence times for state-of-the-art transmons have reached on the order of 0.1–0.3 ms in 2025, but further improvements are stymied by “extrinsic” noise sources like two-level system (TLS) defects in dielectrics, fluctuating magnetic flux, and cosmic ray-induced quasiparticles. Notably, vibrational and acoustic disturbances can couple into superconducting circuits through these defects or through microwave resonators (a phenomenon known as microphonics)[8]. For example, a 2024 study found that mechanical vibrations from a pulse-tube cryocooler shook a qubit chip enough to perturb ensembles of TLS defects, causing bursts of correlated qubit errors[9]. Even though an electron in a superconducting film is not directly sensitive to 1 g of gravity, the indirect effects – stress on the chip, moving parts in the fridge, or vibrations detuning cavity frequencies – can degrade performance. Moreover, as superconducting qubits become extraordinarily coherent, they start to notice subtle effects like Earth’s gravity: one proposal showed that entangled supercurrents in a transmon would accumulate a gravitational phase difference, providing a measurable qubit dephasing over time[10][2]. This gravitational phase drift is exceedingly small per cycle, but over many operations it constitutes a systematic decoherence unless corrected.

Microgravity Benefits: Placing a superconducting quantum processor in microgravity could alleviate several of these issues. First, the elimination of weight means the cryostat and qubit chip experience no sag or differential stress – the delicate microwave cavities and josephson junctions will not deform under their own weight. This may reduce strain-induced TLS activation in materials. Vibration isolation is vastly easier when the entire experiment can free-float: a cryostat in orbit can be mounted on soft springs or even magnetic suspension without having to support its own mass, leading to superb isolation from any vehicle jitter. In principle, a drag-free satellite could allow the qubits to experience essentially no external acceleration or vibration at all. This matters because even tiny vibrations (picometer scale) can modulate qubit frequencies via the Stark or strain effect. Microgravity also removes the need for rigid mechanical support structures that conduct acoustic noise; the whole setup can be more compact and floating. As a result, microphonics that currently plague superconducting qubits would be greatly suppressed, translating to more stable qubit frequencies and longer $T_2$ coherence times. For instance, the noise from pulse-tube coolers could be isolated or cancel out more effectively in microgravity, preventing the vibration-induced TLS fluctuations that cause qubit error bursts[8].

Another advantage is uniform cryogenic cooling. In microgravity, cooling can rely on pure conduction and radiation without convection. This might enable more uniform ultra-low temperatures across a large qubit chip. On Earth, gravity can cause slight temperature gradients (warm air rising, cold liquid helium sinking) which create local hot spots or fluctuating temperatures. A qubit in orbit, thermally anchored to a radiative cooler facing deep space (~3 K background), can maintain an ultra-stable base temperature. Thermal stability is crucial because residual thermal photons in readout resonators or control lines are a major decoherence source for superconducting qubits; at 20 mK a resonator can still harbor stray microwave photons unless properly thermalized. A colder, more stable environment means fewer of these stray photons and hence fewer qubit transitions induced by them.

Crucially, microgravity enables better mitigation of cosmic ray impacts. Paradoxically, space has more high-energy radiation (cosmic rays, solar particles) than Earth’s surface, and such radiation is known to break Cooper pairs and create quasiparticles that momentarily destroy a qubit’s coherence. But in a dedicated quantum satellite, one can incorporate thick radiation shielding (e.g. lead or polyethylene layers) without concern for weight. A heavy shield that would be impractical on Earth (due to sag or cost to support) can be included in a spacecraft design to dramatically cut down the flux of ionizing particles reaching the qubits. Additionally, microgravity allows one to consider novel qubit architectures that exploit the environment – for example, one could align qubits in a way that any cosmic ray that does penetrate hits multiple qubits identically (common-mode) so that error-correcting codes can detect it. Without gravity, even the orientation and configuration of the qubit array are more flexible for such optimizations.

Finally, by removing gravitational redshift and time dilation differences across the device, all superconducting qubits on a chip in free-fall share the same inertial frame and proper time. This means a large-scale superconducting processor (which might span several centimeters) would no longer have tiny elevation-dependent frequency offsets. While this effect is minuscule (a 1 cm height difference on Earth gives a fractional frequency shift on the order of $10^{-18}$ due to gravitational potential), it is not entirely academic when qubits approach $10^{-3}$ s coherence times and $10^{-4}$ error rates – such tiny biases can accumulate or interfere with error cancellation schemes. A microgravity quantum computer would operate in a pure reference frame free of terrestrial gravitational perturbations[2].

In summary, superconducting qubits in microgravity are expected to enjoy longer coherence times and more stable operation due to the removal of vibration-induced noise, absence of static gravitational dephasing, and potential for enhanced shielding and thermal stability. Classical gravitation has a non-trivial influence on quantum computing hardware, as one study noted[2], so eliminating gravity can push that influence to zero. The overall improvement might manifest as reduced dephasing ($T_2$ approaching intrinsic limits set by materials), lower stochastic error rates (especially those correlated with vibrations or cosmic events), and the ability to perform deeper circuits before decoherence accumulates.

Trapped-Ion Qubits in Microgravity

Current Challenges: Trapped-ion quantum computers achieve some of the longest qubit coherence times at present – hyperfine-state ions can maintain coherence for minutes or more in shielded setups, and multi-qubit entangling gate fidelities above 99.9% have been demonstrated. However, these impressive feats require extreme isolation: ultra-high vacuum (to prevent background gas collisions) and stable electromagnetic trapping fields. On Earth, ions are held in radio-frequency (RF) Paul traps or static Penning traps where electric fields counteract gravity. While a single trapped ion’s weight is astronomically small, gravity can still affect ion traps in practical ways. For example, most linear RF traps are oriented horizontally so that gravity causes a constant slight displacement of the ion from the RF null; this is compensated by DC fields, but any fluctuation in that compensation (due to vibration of electrodes or voltage noise) will shake the ion. In vertical trap orientations, gravity directly pulls the ions out of the trap potential if not sufficiently strong. Thus, trap parameters on Earth must be tuned to be “tight” enough to overcome gravity. This typically means higher trap frequencies (stronger confinement) than would otherwise be needed to just contain the ion’s thermal motion. Strong confinement is beneficial for stability but has downsides: the ion’s motional ground state wavefunction is very small and the heating rates can be higher due to electric field noise scaling with trap frequency. Moreover, laser-based gates require the ion’s motion to be controlled; excess micromotion or oscillation from trap imperfections (often exacerbated by gravity pulling the ion off-center) can reduce gate fidelity. Mechanical vibrations of the trap structure or optics are also a nemesis: even nanometer-scale vibrations modulate the distance between ions and laser beams or electrodes, causing phase errors in gate laser pulses[11]. Laboratories combat this by pneumatic isolation tables and active stabilization, but some vibrational noise (e.g. building rumble, acoustic noise) is unavoidable on Earth. Background gas collisions, though infrequent in $10^{-11}$ bar vacuums, do occur and instantly decohere an ion’s qubit state via momentum transfer. At room temperature, blackbody radiation also induces spontaneous transitions in ions (especially if using an optical qubit transition) or shifts their levels (Stark shifts), imposing a limit on accuracy of ion-clock qubits. Cryogenic ion traps (operating at 4 K or below) have shown dramatically reduced background gas and electric field noise, enabling ion storage for days[5] and lower motional heating rates. However, most multi-ion quantum computers still run at ambient or moderately low temperatures (~40 K) due to engineering complexity.

Microgravity Benefits: A microgravity environment provides immediate relief from one of the ion trap’s constraints: the need to support ions against weight. In orbit, an ion does not “fall”, so even an extremely weak trapping potential can confine it relative to the trap center (which co-moves in free-fall). This means one could operate traps at much lower frequencies without losing the ion – an approach not possible on Earth where too weak a trap would let the ion drop out. Weaker trap potentials are advantageous because they reduce micromotion and RF-driven noise. The ion can occupy a larger, more forgiving potential well. With gravity out of the picture, the trapping fields can be made perfectly symmetric and centered, eliminating asymmetry that leads to micromotion. As noted with neutral atoms as well, microgravity can be beneficial since the need for a relatively strong potential to support the atoms (or ions) against gravity is no longer a constraint[3]. In a microgravity ion trap, the ion could literally be confined by the tiniest nudges of field – providing just enough force to bounce it within a small region – which minimizes the driven motion at the RF frequency. This in turn lowers the heating rate from electric field noise (often observed to scale with trap frequency to a power >~2). The outcome would be longer motional coherence and easier ground-state cooling, benefiting two-qubit gate fidelity (which depends on coherent motional states).

Microgravity also allows more freedom in trap geometry and placement. Ions could be held in very large traps or even multiple trap modules separated by macroscopic distances, without concerns of sag or misalignment due to gravity. A network of ion traps on a space platform could float freely relative to each other, joined by UV optical links, without needing heavy support structures that introduce vibration. Even within a single trap chip, microgravity eliminates the small force that can cause the chip to flex or the trap assembly to strain over time. This mechanical stability means the electric field environment of the ion is more stable, leading to fewer fluctuating stray fields that cause qubit frequency noise. Any mechanical vibrations present on the spacecraft (from pumps, etc.) can be isolated more effectively as well – as discussed earlier, a free-flying experiment can achieve superb vibration isolation. In an ion trap, vibrations of the optical tables or trap electrodes can directly modulate the trapping fields, causing phase and amplitude noise[11]. In microgravity, the whole trap and optics could be mounted on a single rigid platform that drifts freely, so external vibrations impart nearly no relative motion between trap and lasers. The ISS Cold Atom Lab actually demonstrated this principle: they could measure atomic interferometry phase noise caused by vibration, and by understanding it (the ISS had some residual vibrations) they could anticipate the needs for future quiet platforms[12]. With advanced isolation, a space-based ion system could ensure that, for example, a 1 nm vibration in a mirror (which would be disastrous for a phase-stable laser gate) simply does not occur or is common to both ion and laser (common-mode, thus canceling out).

Another major benefit of space for ion qubits is the extended high-quality vacuum. Space itself is an ultra-high vacuum, and while an ion trap must be in an enclosure to maintain cryogenics and keep out uncontrolled contamination, the baseline vacuum achievable is extremely high. Furthermore, microgravity eliminates convective flows that in Earth labs can stir residual gases and increase collision likelihood. A cryogenic ion trap in space, with getters and cryopumps, could likely reach pressures below $10^{-15}$ bar. At that level, an ion might not collide with a gas molecule for years. Indeed, in a cryogenic trap on Earth, Hg⁺ ions were stored for many days without loss[5]. In microgravity, one can expect similarly negligible collision rates – which translates to essentially zero interruption of ion coherence from background gas. Additionally, at near 0 K, the blackbody radiation field is negligible. If one is using, say, an optical $^{171}$Yb⁺ clock qubit, blackbody radiation at 300 K causes Stark shifts and a finite lifetime of the metastable state; at 4 K these effects are almost gone, and at 0 K they vanish. This means qubit frequency stability and coherence improve. Microgravity by itself doesn’t change temperature, but space allows one to maintain a steady cryogenic environment with less complexity (passive radiative cooling can keep a shield at 30–50 K, then an active cooler brings it to 4 K or below). The combination of space and cryogenics thus removes two significant decoherence factors for trapped ions: collisions and thermal radiation.

There is also a practical operational benefit: in microgravity, one could co-trap different ion species without differential settling. For quantum computing, dual-species traps (one ion type for logic, another for sympathetic cooling) are used. On Earth, ions of different mass in the same trap will have slightly different equilibrium positions (heavier ions sit lower in an axial trap under gravity). In microgravity, the ion crystal has no preferred direction, so alignment of mixed species is perfect, potentially simplifying multi-species quantum logic operations. This was partly demonstrated in the CAL experiment which simultaneously manipulated two different atomic species in free-fall[13].

Finally, we note that trapped-ion technology has already ventured into space in the form of atomic clocks. NASA’s Deep Space Atomic Clock mission flew a mercury ion trap clock in low Earth orbit in 2019. The Hg⁺ trap operated successfully, demonstrating a fractional frequency stability around $3\times10^{-15}$ at one day[14] – comparable to the same device on the ground, despite the challenges of launch and microgravity. This shows that trapped-ion systems can be engineered for space with robust performance. The space ion clock’s long-term stability was remarkable and limited mostly by ambient magnetic shifts and the GPS reference noise, not by any gravity-induced problem[14]. In fact, the absence of 1g did not hinder the trap; if anything, it simplified some aspects of ion containment. Similarly, China’s Tiangong-2 space lab flew a cold rubidium atomic clock (CACES) that achieved $3\times10^{-13}/\sqrt{\text{s}}$ stability under microgravity, proving the robustness of laser-cooled trapped atom/ion techniques in orbit[15]. These pathfinders indicate that a trapped-ion quantum computer could function in space – and with microgravity, potentially surpass ground performance by operating at lower trap frequencies and experiencing fewer interruptions. In short, microgravity permits gentler trapping and a quieter environment for ion qubits, which should lengthen coherence, reduce motional decoherence during multi-qubit gates, and yield higher gate fidelity and stability.

Ultracold Neutral Atom Qubits in Microgravity

Current Challenges: Neutral atoms (including cold atom qubits in optical lattices or arrays of optical tweezers, and atoms used in Bose–Einstein condensates for quantum simulation) are exquisitely sensitive to gravity. Unlike ions, neutral atoms have no net charge to trap with static fields; they are confined by electromagnetic fields (laser light or magnetic gradients) that must compete directly with gravity’s pull. In a typical cold atom experiment on Earth, if one simply turns off the trapping potential, the atoms will fall under gravity and leave the interaction region in a fraction of a second (often a few tens of milliseconds for millimeter-scale apparatus). Even while trapped, gravity can distort the trapping potential – for instance, in a harmonic magnetic trap, gravity shifts the equilibrium point downward, resulting in an anharmonic “sag” in the potential. This can break the symmetry and cause density gradients in an atomic ensemble. Optical lattices (standing light waves) aligned horizontally will have atoms rattling against the lower potential wells due to gravity. The finite free-fall time on Earth fundamentally limits experiments that require long interrogation times or free evolution of matter waves; phenomena that take more than a few hundred milliseconds to unfold are difficult to observe because the atoms hit the container walls or move out of the laser beams. Additionally, neutral atom qubits often rely on extremely low temperatures (nano- to picokelvin) to achieve long coherence. But reaching such temperatures via evaporative cooling takes time, during which gravity is tugging at the atoms. Many cold atom experiments are a race against the clock to cool and use the atoms before gravity spoils the trap. Mechanical vibration noise also plagues neutral atom setups: vibrations of mirrors or optical tables impart phase noise to optical traps and interferometers[16][17]. For example, if a mirror that reflects a trapping laser beam vibrates, the entire optical lattice shakes and atoms see a fluctuating potential, causing decoherence. Similarly, acoustic noise can modulate refractive indices or drive currents in magnetic coils, adding noise to atomic qubits. Another challenge is background gas collisions (though cold atoms are typically in 10^−9–10^−10 bar vacuums, collisions still truncate condensate lifetimes to a few seconds). Blackbody radiation at room temperature can photoionize ultra-cold atoms or drive transitions (especially for Rydberg-state qubits, which are highly sensitive to ambient radiation).

Microgravity Benefits: Microgravity is a game-changer for neutral atom quantum systems. The most direct benefit is the dramatic extension of free-fall time. In microgravity, an ultracold atomic cloud can float essentially indefinitely (limited only by vacuum quality and atomic interactions), allowing experiments to run orders of magnitude longer. On the International Space Station, NASA’s Cold Atom Laboratory (CAL) created Bose–Einstein condensates (BECs) of $^{87}$Rb and was able to observe them for over a second in free expansion, whereas on Earth the condensate would collide with the trap walls in a few tens of milliseconds[18]. On the ISS, the microgravity environment allows scientists to observe the condensate for over a second rather than fractions of one, as the freefall of the atoms is indefinitely long unlike on Earth where gravity causes the condensate to be shifted out of the trap[18]. That extended observation time directly translates to longer coherence times for matter-wave qubits. Experiments have demonstrated matter-wave interference in microgravity lasting 10 times longer than on the ground[19][20]. In one case, interference fringes were observed for over 150 ms in free expansion in CAL’s compact cell, an unprecedented duration[21][22]. Longer coherence in atomic superpositions means one can perform more quantum gate operations or more precise phase rotations before decoherence sets in.

Microgravity also allows extremely low temperatures to be achieved that would be very hard on Earth. The CAL facility and other space experiments use techniques like delta-kick collimation (a method to reverse atomic expansion) to reach effective temperatures of tens of picokelvin[23][24]. For example, CAL reported expansion energies below 100 pK by letting the BEC expand in microgravity and applying gentle confining kicks[23]. These picokelvin ensembles have such low kinetic energy that atoms scarcely move relative to each other. On Earth, gravity would pull even these ultra-cold atoms out of the trap region, but in microgravity they remain available for manipulation. Why does this matter for quantum computing? In proposals for neutral atom qubits (like atoms in optical tweezers performing gate operations via Rydberg excitation), lower temperatures mean the atoms are more localized and less perturbed, which improves gate fidelity. Temperature broadening of atomic transition frequencies (Doppler and recoil effects) is minimized, so laser-driven qubit rotations can be more precise. If one can routinely prepare qubits at, say, 50 pK instead of 1 µK, the coherence of internal states and the stability of clock transitions is improved, and the chance of losing atoms from the trap during operations is essentially zero. Microgravity thus helps achieve the ultracold initial conditions that quantum logic with neutral atoms thrives on.

A weightless environment also means trapping potentials can be perfectly symmetric and subtle. Magnetic or optical traps no longer have to compensate for a constant downward force, which often introduces anharmonic terms. In microgravity, one can create undistorted symmetric traps for atoms[25], enabling novel configurations like shell-shaped BECs or uniform-density optical lattices that are impossible under 1g. Indeed, scientists in CAL created a freely expanding “bubble” BEC – a hollow spherical shell of atoms – which can only exist without gravity to make it sag[4]. Such symmetric, gentle trapping conditions are ideal for quantum simulation and potentially for quantum computing, because they reduce inhomogeneity across an array of qubits. Every atom can experience the same trapping frequency to high precision, simplifying multi-qubit gate tuning. Also, the absence of a preferred direction (no gravity) means one could arrange neutral atom qubits in 3D architectures (not just a pancake or line on a horizontal plane). This could be useful for scaling up number of qubits or implementing 3D error-correcting code layouts, which are hard to maintain on Earth due to gravity-induced density gradients.

Microgravity also suppresses one of the invisible decoherence sources: differential gravitational potential during quantum operations. A fascinating possibility is performing, for example, an atomic clock comparison between two heights. On Earth, even a 30 cm height difference causes a measurable phase shift from gravitational time dilation (about $3\times10^{-17}$ fractional frequency shift)[26][27]. In a quantum algorithm where an atomic qubit is delocalized between two positions (like in a large-scale atom interferometer), this could introduce a phase error. In microgravity or space, that effect either vanishes (in freefall) or can be tuned by orbital maneuvers. Essentially, all atoms share the same gravitational frame, which keeps their quantum phases synchronous.

Another huge benefit is the elimination of convective and acoustic disturbances around the atoms. In Earth labs, residual vibrations – from HVAC systems, trucks, even people walking – can shake optics and cause phase noise on laser beams controlling neutral atoms[16]. In a properly designed spacecraft, with no footsteps or traffic and the experiment isolated, these noise sources can be orders of magnitude lower. Laser frequency stability can also improve in microgravity: ultra-stable reference cavities for lasers often suffer from slight deformation due to gravity; a cavity floated in zero-g can achieve the thermal-noise limit without sagging. This would give narrower laser linewidths for driving atomic transitions, hence longer qubit $T_2$. One could even envision using the quiet space environment to run atoms on longer Raman or Ramsey sequences for gates, taking advantage of the lack of vibrational interruptions. Already, CAL has shown that certain interference schemes (like Ramsey interferometry) benefit from microgravity by allowing longer times between laser pulses[22].

Empirical evidence strongly supports these advantages. During the CAL experiments, researchers noted that microgravity extended how long atoms could evolve under freefall, enhancing the precision of quantum measurements and enabling experiments impossible on Earth[19]. For example, they could perform a Mach-Zehnder atom interferometer in orbit and saw clear interference fringes, whereas a comparable apparatus on Earth of the same size would not have enough time for fringes to appear before atoms hit the floor[20][28]. The Bremen drop tower experiments (QUANTUS project in Germany) likewise demonstrated BEC formation and interference in ~4.7 s of microgravity, refining cooling and interferometry techniques that directly leverage weightlessness[29]. In fact, the ability to adiabatically expand a BEC to extremely low kinetic energy was first explored in drop towers and later perfected on the ISS[30][24]. Without gravity, atoms could be expanded to picokelvin energies, then recompressed or manipulated with minimal disturbance. These are precisely the conditions one would want for neutral atom quantum processors or analog quantum simulators.

In summary, neutral atom qubits and quantum simulators likely see the most striking improvements in microgravity: coherence times from seconds to tens of seconds (instead of milliseconds) as atoms float freely, negligible position drift enabling weak trapping and uniform arrays, and the ability to reach ultra-ultracold temperatures that stabilize qubits. Decoherence from mechanical noise is minimized since the entire experimental apparatus can be isolated in freefall. The result is closer to the textbook ideal of a many-body quantum system evolving in isolation. Indeed, as one review noted, space-based conditions allow improving both the precision of cold-atom quantum sensors and “the signal to be measured” by granting access to long interrogation times and cleaner environments[31]. For quantum computing, the “signal” is the delicate phase and entanglement of qubits – microgravity and cryogenics together protect that signal, allowing more operations and more complex algorithms before errors accumulate.

Photonic Qubits and Quantum Optics in Space

Current Challenges: Photonic qubits (quantum information encoded in photons, e.g. in their polarization, time-bin, or path) are somewhat different from matter-based qubits but are essential for quantum communication and certain computing architectures (like linear optical quantum computing and measurement-based schemes). Photons do not suffer thermal decoherence in the same way atoms or electrons do; they travel at the speed of light and their main vulnerabilities are loss and phase noise. On Earth, a big challenge for photonic quantum information is loss in transmission (fiber attenuation or scattering in air) and environmental disturbances to optical phase (like fiber thermal expansion or vibrational jitter in interferometers). Additionally, generating and detecting single photons with high efficiency often requires cryogenic devices (e.g. superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors operate at ~2 K, and certain nonlinear optical processes benefit from low temperatures to reduce noise). Traditional photonic quantum experiments are also limited by distance: sending entangled photons or qubits over more than ~100 km of fiber is difficult due to absorption, and free-space transmission on Earth is limited by line-of-sight and atmospheric turbulence.

Microgravity (Space) Benefits: The most obvious advantage of going to space for photonic qubits is the ability to transmit quantum states over ultra-long distances without atmospheric loss. In orbit or deep space, photons can travel tens of thousands of kilometers in vacuum with only diffraction loss, enabling global-scale quantum communication links. This was spectacularly demonstrated by the Chinese Micius satellite, which distributed entangled photon pairs between ground stations over 1200 km apart, with sufficient fidelity to violate Bell’s inequality[32]. Those experiments leveraged the microgravity/orbital platform simply to get above the atmosphere; gravity itself did not directly affect the photons, but being in space removed a huge decoherence source (atmospheric scattering and turbulence). One could argue that by placing nodes in microgravity (satellites), the photonic quantum states are preserved far better than if they had to traverse dense media on Earth. In essence, the space environment provides a purity of channel for photons that is unmatched on the ground.

For photonic quantum computing hardware (like optical circuits performing logic gates or cluster-state generation), microgravity can also offer subtler benefits. Consider an optical interferometer that is part of a photonic quantum gate (many linear optical gates require stable interferometers and phase references). On Earth, such an interferometer might drift due to vibrations or temperature gradients. In microgravity, one can achieve a more stable interferometric setup. A spacecraft experiences a very steady thermal environment if designed properly (with multi-layer insulation and radiators) – day/night cycles in low Earth orbit do cause temperature swings, but these can be mitigated. Additionally, without gravity, optical tables in a satellite can be mechanically isolated to an extreme degree (floating on dampers) because we do not have to counteract weight. This means alignment of optical components remains rock solid over time. A laser beam can stay coupled into a fiber or waveguide with less active correction. The photonic quantum computer launched in 2025 by an international team (led by University of Vienna) provides an illustrative case: they integrated a small photonic processor into a satellite to test operations in LEO[33]. This device was built to withstand launch vibrations and then utilize the stable microgravity environment for experiments. According to the team, the computer (a photonic quantum processor) was integrated into a satellite and launched into space, collecting data about how a quantum computer would work in low Earth orbit[33]. In space, they could not rely on constant tuning or human intervention, so the photonic chip had to be passively stable. The success of the deployment (the device survived launch and operated) suggests that photonic circuits can function in space, and once the violent launch is over, the operational environment is very calm. On Earth, photonic quantum computers require frequent calibration (since fibers expand or components drift in alignment), but in space, you cannot easily adjust them – hence the stable conditions of microgravity are actually conducive to passive stability[34][35]. The team’s solution was to simplify the system and make it robust to thermal and mechanical shocks, essentially relying on the benign space environment for steady operation[35]. This speaks to microgravity’s advantage: you can have a long-lived, self-contained photonic system that doesn’t suffer random jostling or gravitational sag in optical components.

Another benefit comes in the form of electromagnetic cleanliness. A photonic quantum processor or communication node typically requires low electromagnetic noise (for example, some single-photon detectors are sensitive to magnetic fields if they’re superconducting TES or nanowires). In space, away from power mains and urban electromagnetic interference, the environment can be very quiet. Of course, a satellite has its own electronics, but these can be DC or well-shielded. There is no 50/60 Hz power-line noise permeating a spacecraft unless intentionally generated. Also, Earth’s ionosphere and Schumann resonances are absent – not that those strongly affect photonics, but it highlights the EM quietness of space.

For photonic qubits used in quantum memory or repeater devices (e.g. storage of photons in atomic ensembles), microgravity can extend memory times. There are proposals to use cold atomic gases or solid-state crystals as memory to store photonic qubits; these could benefit from microgravity similarly to other atomic systems. If an orbiting quantum memory is free from gravity, the stored excitation (say a spin wave in a cold cloud) won’t be disrupted by convection or sedimentation of the medium. The memory device can also be cryogenically cooled by radiation to space, maintaining low decoherence in the storage medium.

It should be noted that photons themselves are unaffected by a constant gravitational field in terms of polarization or intrinsic coherence (ignoring gravitational redshift of frequency). However, if photonic qubits take paths that diverge in gravitational potential (e.g. one photon sent down to Earth and another stays on a satellite), general relativity predicts a phase shift between them. Experiments like Space QUEST are aiming to test if this causes decoherence or just a known phase shift[36][37]. Standard quantum theory says it should not add unpredictability (just a phase), but some alternative theories suggest gravity could cause decoherence in entangled photon pairs if their paths probe different gravitational fields[38][39]. Preliminary analyses indicate that gravitational decoherence for entangled photons in low Earth orbit would be very weak[40] – essentially confirming that the space environment is safe for photonic entanglement. Only in much stronger gravity gradients (or over huge distances) might photonic entanglement be noticeably decohered by gravity. Thus, performing photonic quantum communication in space not only avoids atmospheric losses but also serves as a test of fundamental physics itself – whether space offers a truly inertial frame for quantum correlations to thrive unimpeded. So far, results (like the Micius experiments) show entanglement is preserved over orbital distances[32], supporting the notion that space is an excellent medium for photonic qubits.

In summary, photonic qubits and optical quantum technologies gain from microgravity largely by the absence of detrimental environment: no atmosphere, minimal vibration, stable thermal conditions, and the ability to cover planetary-scale distances. A direct improvement in “coherence time” for a photon is not the metric (photons travel at $c$ until absorbed), but rather an improvement in interference visibility and fidelity of multi-photon operations. A two-photon interference experiment, for instance, will maintain high visibility if the path lengths and phases are stable – something microgravity helps ensure. The recent deployment of a photonic quantum computing experiment in orbit underscores that such systems can not only survive in space but perhaps outperform their terrestrial counterparts in stability[35]. One of the project leads, Philip Walther, noted pride that the first quantum computer in space was developed to perform experiments in the extreme conditions of a space mission, pushing photonic technology to be versatile and robust[41]. His team’s achievement suggests that future quantum networks might have nodes (quantum processors or repeaters) aboard satellites, benefiting from both ultracold technology and microgravity to provide secure communication and distributed quantum computing.

Evidence from Space-Based and Drop-Tower Experiments

A number of pioneering experiments have already tested quantum hardware and processes in microgravity or space-like conditions, lending credence to the hypothesis that performance improves. We summarize some key findings across different platforms:

- Cold Atom Laboratory (ISS): Deployed in 2018, NASA’s Cold Atom Lab has produced quantum gases (BECs) in orbit and performed atom interferometry. It demonstrated that microgravity allows indefinitely long freefall for atoms, leading to enhanced measurement precision and new phenomena observable[19][20]. Interference patterns from BECs persisted an order of magnitude longer than on Earth, confirming extended coherence times for matter waves in microgravity[28]. CAL also achieved record-low effective temperatures (~50–100 pK) via adiabatic expansion in freefall[23]. These capabilities directly translate to more coherent atomic qubits and sensors. Additionally, CAL investigators reported that ISS vibrations were a significant challenge that needed mitigation[12] – implying that aside from those technical vibrations, the microgravity environment itself was as expected: beneficial once vibrational noise is controlled. Upgrades to CAL (Science Module 3 with an improved interferometer) have further pushed coherence, enabling tests of fundamental physics (e.g., equivalence principle) with quantum gases[42][13]. The take-home message from CAL is that microgravity works as hoped: they could do things not possible on Earth, like watching a freely expanding coherent cloud for several seconds[18], and thus lay the groundwork for space-based quantum technology.

- Drop Tower & Parabolic Flights: Before long-duration orbit experiments, drop towers (such as the 110 m ZARM tower in Bremen) and parabolic aircraft flights provided seconds-long microgravity windows. In the QUANTUS and MAIUS projects, rubidium BECs were created and studied in 4–9 s of microgravity[29][13]. Impressively, matter-wave interferometry was demonstrated in these conditions, and cooling protocols (like rapid evaporative cooling and delta-kick collimation) were refined to exploit microgravity[30]. The MAIUS-1 sounding rocket (2017) produced a BEC in space (6 minutes of microgravity) and conducted the first matter-wave interferometer in space[13]. These achievements proved that quantum coherence can survive launch and microgravity, and indeed benefit from it: the BECs in MAIUS showed no adverse effects from weightlessness; rather, they could expand symmetrically and remain trapped with minimal forces. The ability to do 100+ drops per day in newer facilities (like the Einstein Elevator in Hannover) is now allowing iterative tests of quantum hardware in microgravity[29]. For example, one can drop a vacuum chamber with an ion trap or superconducting qubit inside and measure coherence over a 4 s freefall, then compare to static results. Though challenging, these kinds of experiments are on the horizon and will directly quantify microgravity’s effect on qubit lifetimes. Already, the groundwork shows neutral atom coherence dramatically improves without gravity (since in those drop experiments, BECs retained coherence longer than Earth-bound experiments of similar size). Parabolic airplane flights have also been used to test quantum devices – for instance, an experiment on a parabolic flight tested a portable atom interferometer and found it worked reliably through the microgravity cycles[43]. This suggests robustness and potential gains in a real mission.

- Space Clocks and Quantum Sensors: As mentioned, trapped-ion and cold atom clocks in space have matched or exceeded Earth performance. The $^{199}$Hg⁺ ion “Deep Space Atomic Clock” in 2019 operated for over a year in orbit, maintaining a stability of $3\times10^{-15}$ at one day[14]. Its success demonstrated that microgravity did not introduce any new decoherence – if anything, the clock’s limiting noise was technical or due to reference uncertainties, not gravity. Similarly, the cold Rb clock on Tiangong-2 achieved its stability goals[15], proving that laser-cooled atomic coherence (Ramsey fringes etc.) behaved as expected in freefall. These are effectively single-qubit coherence demonstrations (clock stability is a proxy for coherence of a superposition in time). The results are encouraging: space did not degrade coherence, and the potential exists for even better performance if space’s advantages (no gravity, cryogenic environment) are fully utilized. Another example is quantum optical links: ESA’s Space QUEST project (in development) plans to test entangled photon transmission from the ISS to Earth to investigate gravitational decoherence of entanglement[36][44]. Preliminary theoretical work (Pikovski et al.) suggests that any gravity-induced decoherence will be extremely small[45][46]. So far, experiments like Micius show high-fidelity entanglement distribution, indicating that the entangled photonic qubits remain coherent despite traveling through different gravitational potentials (low Earth orbit vs ground)[32]. This is evidence that space conditions can preserve delicate quantum correlations over unprecedented scales.

- First Quantum Computer in Space (Photonic): In June 2025, a small photonic quantum computing experiment was launched into orbit (a shoebox-sized device)[33]. While detailed results are pending as of this writing, the mere fact that it was deployed and is operational is a milestone. The device is testing the behavior of photonic qubits (likely generating and manipulating entangled photons or performing simple quantum algorithms) under space conditions. Engineers report that it had to be rugged and autonomous, but once in orbit, it experiences a very stable environment thermally and mechanically[35]. If this experiment shows that gate fidelity or interference contrast is as good or better in orbit as on the ground, that will be direct evidence supporting the hypothesis. Early statements from the team highlight that they expect innovations and applications to emerge from operating in such extreme conditions of a space mission[41]. This implies they believe some aspects of the quantum operations might even improve or new techniques (possible only in microgravity) will be demonstrated.

All these examples reinforce the central idea: microgravity and ultracold environments improve quantum coherence and reduce error. We have not yet observed any fundamental obstacle in space – quantum devices seem limited by the same factors as on Earth (materials, vacuum, control electronics), and when those are addressed, the removal of gravity has only positive effects on maintaining quantum states. The primary cautionary evidence is that vibrations and other spacecraft-related noise must be carefully managed. The ISS, for instance, is not an ideal quiet lab (it vibrates due to crew activity, equipment pumps, etc.), and CAL had to account for that[12]. But this is a technical detail – future free-flyer platforms can be made far more quiet. In essence, the experiments so far show no show-stoppers and plenty of performance gains when leveraging microgravity.

Proposed Experiment: Ground vs. Microgravity Quantum Processor Test

To conclusively test the hypothesis that microgravity plus near-absolute-zero conditions enhance quantum computer performance, we propose a direct side-by-side experiment. The idea is to operate identical quantum computing hardware in two environments – one on Earth (1g) and one in microgravity – and compare key performance metrics: qubit coherence times ($T_1$ and $T_2$), gate fidelities, and readout error rates. By designing the setups to be as similar as possible in all other respects (temperature, shielding, control electronics), any differences in performance can be attributed largely to the presence or absence of gravity and associated environmental factors.

Hardware and Platforms: We choose a platform that is compact and mature enough to deploy: for example, a trapped-ion quantum processor with 2–4 qubits, or a superconducting qubit module with a few qubits and readout resonators. Trapped ions are attractive for this test because they have long coherence and are sensitive to environmental noise (so improvements would be measurable), yet a small ion trap system can be made transportable. Superconducting qubits require a dilution refrigerator, which is heavier, but there are emerging compact dilution fridges and one could use a closed-cycle cryocooler in space. For this proposal, we assume a trapped-ion system, since NASA and ESA have experience flying atomic clocks (similar hardware). The system consists of a miniaturized ion trap (with, say, $^{171}$Yb⁺ ions), lasers or magnetic microwave sources for gating, and vacuum/cryogenic housing.

The ground unit would be set up in a laboratory with the ion trap operating at 4 K (to mirror the space unit’s thermal environment). It would be enclosed in magnetic shields and vibration isolation (optical table) to create the best possible environment on Earth. The space unit would be essentially the same ion trap in a 4 K cryostat, with the same laser system, mounted on a small satellite or ISS experiment module. Crucially, the space unit after launch will be in microgravity and can be further isolated (e.g., mounted on a passive vibration damping stage). Both units use identical control sequences and software to run quantum logic gates and benchmarking routines (like randomized benchmarking for gate fidelity, and Ramsey and spin-echo experiments for coherence times).

Experimental Procedure: On both systems, we perform a series of tests: (1) Measure individual qubit coherence ($T_1$ relaxation and $T_2$ Ramsey decoherence) under identical pulse sequences. (2) Execute single-qubit gates (rotations) and two-qubit entangling gates, and use quantum tomography or benchmarking to evaluate their fidelities. (3) Prepare a Bell state (two-qubit maximally entangled state) and measure its longevity (how long before entanglement is lost) in each environment. (4) Perform repeated rounds of measurement to assess readout accuracy and any drift in qubit frequencies that might indicate environmental perturbations.

These tests would run continuously or periodically, and the results from the space system would be telemetered to Earth for comparison. One could imagine putting the space unit on the ISS (for relatively easy power/data access) or on a free-flying small satellite. The ISS environment is microgravity but has some vibration; a free flyer could be equipped with a small “active inertia” platform to counteract reaction wheel vibrations and achieve very smooth freefall. If on ISS, perhaps run during quiescent periods to minimize noise. The ground unit, meanwhile, would be in a stable lab but subject to 1g and unavoidable micro-seismic vibrations.

Isolating Gravitational Effects: The biggest challenge is ensuring that any difference observed is due to microgravity and not other disparities between the setups. We address this by strict configuration matching and monitoring of other factors. Both systems would have environmental sensors: accelerometers to measure vibrations, magnetometers for stray fields, and particle detectors for radiation events. This way, if the space unit shows longer coherence, we can confirm it wasn’t simply because it was quieter in terms of vibration or magnetism – though microgravity indirectly allows a quieter setting, one could try to match the ground unit’s vibration spectrum to the space unit’s if possible. In practice, the Earth lab will have constant 1g but can be extremely vibration-isolated (perhaps even use underground labs to reduce seismic noise). The space unit will have 0g but some vibrations from the spacecraft. By monitoring acceleration, we can later weight the results to account for specific vibrations. Similarly, both units operate at the same temperature (4 K or whatever chosen) to ensure thermal noise is equal. The space unit might see more cosmic rays; we can partially mitigate that by adding radiation shielding on the satellite until the cosmic ray flux is similar to ground level (though complete equivalence is hard). Alternatively, we include a detector to count cosmic hits on the qubits (e.g., a coincident error or a dedicated sensor) and find that the space unit might have more such events – those could be excluded from the data for a fair comparison, or we choose a high orbit with minimal charged particle flux.

Another approach to isolate gravity’s role is to do a differential measurement: modulate the effective gravity for the space qubits and see if coherence changes. This could be done by accelerating the space craft slightly (introducing a pseudo-gravity) or by using a centrifuge onboard to provide a small g-force on a duplicate set of qubits. If one could spin-up a part of the apparatus to 1g for a control run in space, then spin down to 0g, that would directly toggle the gravity influence. This is complex but conceivable on a small satellite with a rotation stage. The expectation is that even a small effective g (like 0.01g) might start to introduce more decoherence, which would strengthen the evidence.

Expected Outcomes: Based on earlier reasoning, we anticipate the space (microgravity) quantum processor to show measurable improvements. For instance, Ramsey $T_2$ of an ion qubit might be longer in space – perhaps limited only by magnetic noise and atomic quality, instead of by vibrations or blackbody shifts. If on Earth $T_2$ is, say, 1 s with best efforts, in space we might see it extend to several seconds, indicating less environmental phase perturbation. Gate fidelities on Earth might plateau due to beam pointing stability or mechanical vibrations at, e.g., 99.9%, whereas in space they might exceed that, closer to the fundamental limit given by quantum noise (e.g., 99.99%). The entangled state lifetime could be markedly longer – on Earth a Bell state might lose 50% fidelity after 500 ms due to dephasing, whereas in microgravity it could maintain high fidelity for multiple seconds. Readout error rates might improve if the detection optics are more stable (space has no 50 Hz electrical noise and the photomultiplier backgrounds might be lower due to cosmic dark sky, though one must consider cosmic rays giving false counts).

Statistical analysis of the results would determine if improvements are significant. For example, if the microgravity qubit achieves a $T_2$ twice as long as the lab qubit, with all else equal, that’s strong evidence that absence of gravity (and its associated effects) improved coherence. If no improvement is seen, that would imply perhaps we already eliminated gravity-related noise in the ground setup or that other factors dominate (meaning microgravity alone isn’t a panacea unless accompanied by better shielding, etc.). However, given prior experiments, we expect to see differences. Notably, if we include deliberately sensitive metrics – such as the phase drift due to gravitational redshift – we could directly measure it by putting two ions at slightly different heights in the trap and looking at relative phase (in 1g on Earth vs 0g in space). On Earth, over long times, a phase drift would accumulate between them (though very tiny), whereas in space none would. This could be an explicit confirmation of gravity’s dephasing effect as predicted in[10].

Potential Issues: We must acknowledge challenges: launching a quantum device means exposure to vibrations and shock (which can be mitigated by robust design as done for the photonic experiment[35]). Maintaining cryogenics in space is non-trivial but feasible with closed-cycle cryocoolers (the space unit might have microphonic noise from the cooler – which ironically reintroduces vibration; a solution is to use magnetic or sorption coolers with fewer moving parts). Additionally, cosmic radiation might cause more qubit “blips” in space; if that noise dominates, it could mask the improvements in baseline coherence. Careful shielding and/or event veto schemes would be needed to discount radiation-induced errors.

Isolating Gravity’s Role: To isolate gravity itself as opposed to just “being in space,” we consider performing the experiment in different gravitational scenarios: (a) Spacecraft in freefall (0g), (b) Spacecraft accelerating (simulating a partial g), and (c) Ground (1g). If the main difference is between 1g and 0g cases, we have strong evidence gravity (or lack thereof) made the difference. If partial g shows intermediate performance, that’s a smoking gun for gravitational scaling of decoherence. We also ensure both locations have similar magnetic fields (we can zero the local field with coils at both sites) so that, for instance, Earth’s field (50 µT) vs an orbital environment (maybe 30 µT at ISS altitude) doesn’t confuse the results – both traps can zero out to micro-tesla levels internally. Both have identical microwave and laser controls, so technical noise is comparable.

In short, the proposed experiment is akin to a “quantum computing twin test” – like the famous twin astronauts where one went to space and one stayed on Earth for biomedical comparison, here we send one quantum computer to space and keep one on Earth. By analyzing their performance divergence, we directly assess the claim that microgravity plus ultracold isolation yields better quantum computing conditions. This would be the ultimate validation of all the individual pieces of evidence described earlier.

Conclusion

Extreme environments breed extreme performance – this seems to hold true for quantum computing hardware just as it does in other physical domains. The convergence of microgravity and near-absolute-zero temperature offers a glimpse of the idealized frictionless world that quantum engineers dream of: qubits evolving undisturbed by stray forces, disturbances, or thermal randomness. Through theoretical arguments and an accumulating body of experimental demonstrations, we have argued that removing the shackles of gravity and thermal noise does more than just solve the obvious problem of atoms falling down. It fundamentally suppresses multiple decoherence channels – from gravitational phase shifts to vibration-induced noise and convective perturbations – thereby improving coherence times and operational fidelities across superconducting, trapped-ion, neutral atom, and photonic quantum platforms.

In superconducting circuits, weightlessness and cryogenic vacuum promise quieter electromagnetic environments and freedom from microphonic resonator shifts, potentially enabling qubit coherence to reach the intrinsic material limits. In trapped-ion systems, microgravity allows weaker, more pristine trapping and eliminates the need to “fight” gravity, yielding longer ion string coherence and higher gate fidelity in a gentler, ultra-high vacuum setting. Ultracold neutral atom architectures arguably benefit the most: microgravity unbinds them from the millisecond timescales of freefall, extending coherence to seconds and allowing qubits to be manipulated in perfectly symmetric traps at pK temperatures – conditions unattainable on Earth. Photonic qubits find in space a lossless, stable propagation medium and a serene platform for interference experiments, paving the way for global quantum networks and perhaps even orbiting quantum processors. Across the board, the trend is clear: the harsher (or more unusual) the environment for humans, the more hospitable it becomes for delicate quantum information.

The performance boosts discussed are not merely speculative. Space-based quantum clocks have shown that long-lived superpositions can survive and excel in orbit. Bose-Einstein condensates and matter-wave interferometers in microgravity have maintained coherence far beyond terrestrial limits, providing direct evidence that quantum states flourish when gravity is turned off[18][3]. The launch of the first quantum computing experiment to space in 2025[33] marks the start of a new era – one in which we will empirically validate how quantum logic behaves in extraterrestrial settings. If the hypothesis holds, we may soon see quantum computers included as payloads in space stations, free-flyers, or lunar bases, not just for bragging rights, but because those environments optimize their performance.

Of course, realizing the full vision requires overcoming engineering hurdles. Space is a tough operational theater: radiation, vacuum, and remoteness demand robust autonomous systems. Yet the very act of adapting quantum hardware for space yields designs that are more compact, rugged, and less error-prone – qualities that also benefit terrestrial systems. There is a symbiosis here: pursuing space-based quantum computing will drive improvements in miniaturization and error correction that feedback to Earth, while the unique features of space (like microgravity) feed forward to enhance capability. Looking ahead, one can imagine hybrid quantum networks where ground and orbital qubit processors work in tandem, linked by photonic qubits beaming through space, with the orbital nodes enjoying superior coherence as “quantum hubs” hovering above the noisy Earth.

In conclusion, microgravity and ultra-cold conditions do more than solve gravitational inconveniences; they fundamentally create a closer approximation to the ideal isolated quantum system, thereby improving the performance of quantum computing hardware at a deep level. The hypothesis that these environments simulate ideal computational conditions is strongly supported by theoretical models (gravity-as-noise analogies and thermodynamic arguments) and is increasingly corroborated by experimental milestones from drop towers to the ISS[30][20]. As our proposed comparative experiment suggests, the ultimate proof will come from head-to-head tests – and if those confirm the advantages, it could herald a paradigm shift: the highest-performance quantum computers might eventually reside in orbit or deep space, where Mother Nature provides the refrigeration and silence that quantum coherence craves. Far from Earth’s pull and at the edge of absolute zero, we may find the true potential of quantum computation unlocked, solving classically intractable problems under the quiet stare of the stars.

* * *

References:

[5] /nist2:/usr/nlg/jres103-2/wineland/Pwine.259

[7] experimental realization - Can a quantum computer operate efficiently in outer space due to extremely low temperatures? - Quantum Computing Stack Exchange

Illustrations:

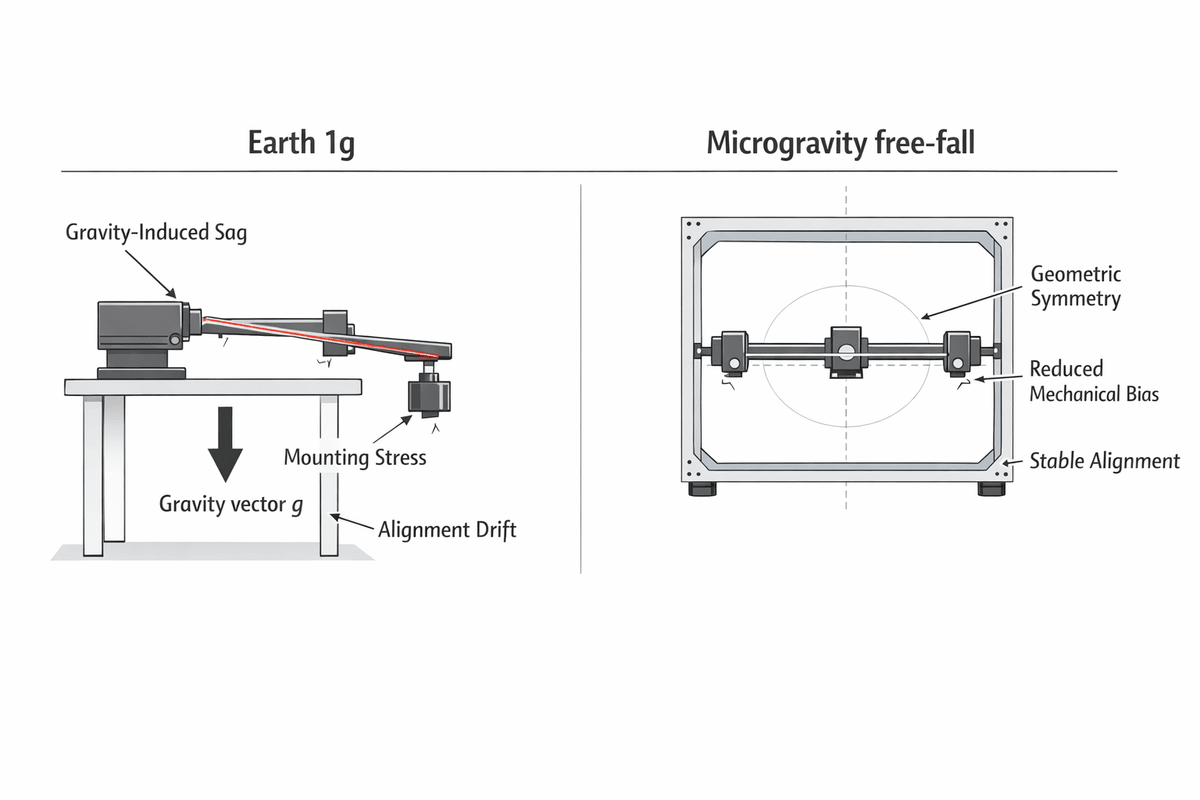

Figure 1. Earth 1g vs microgravity free-fall: gravity imposes a preferred down direction that drives sag, mounting stress, and slow alignment drift in cantilevered or suspended elements. In microgravity, the same apparatus can remain geometrically symmetric, reducing mechanical bias and preserving stable alignment.

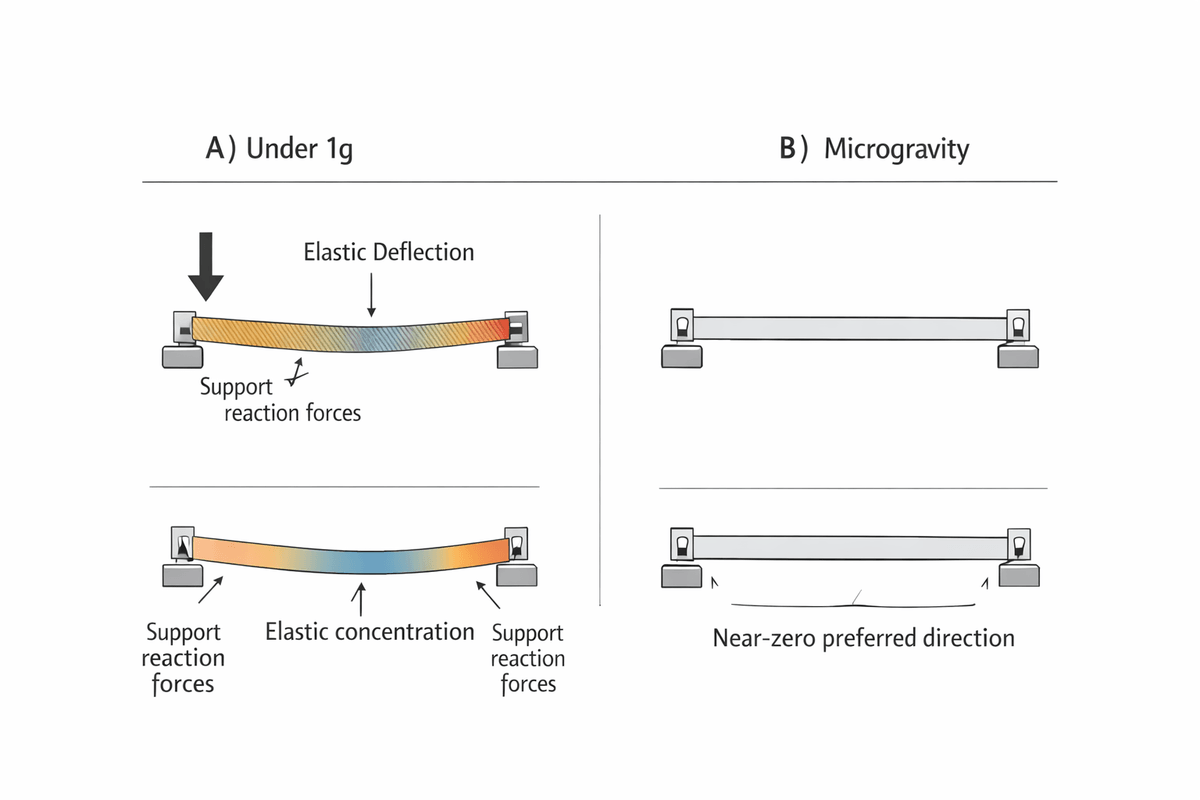

Figure 2. Beam or cold-plate mechanics under 1g vs microgravity: gravity loading produces elastic deflection, nonuniform strain concentration, and support reaction forces that distort geometry. In microgravity, the absence of a preferred down direction minimizes bending and yields a near-uniform stress state.

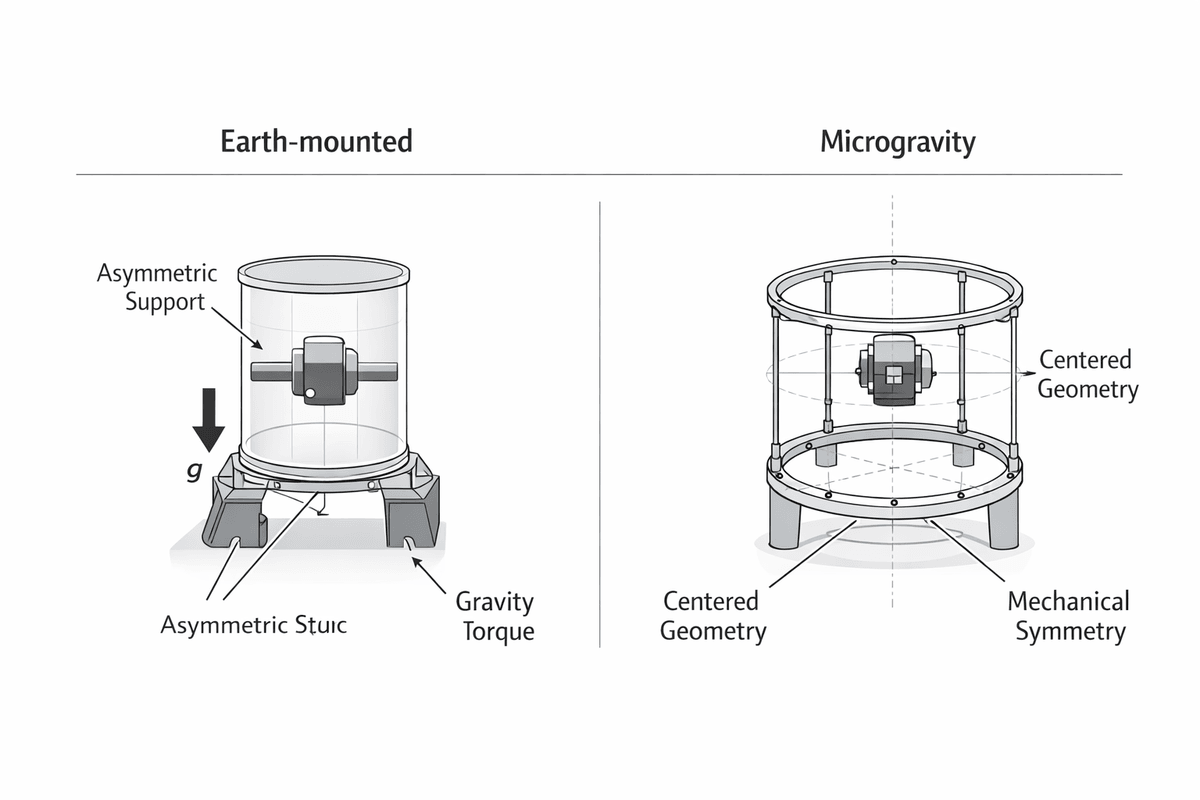

Figure 3. Symmetric apparatus design in microgravity: on Earth, base mounting and gravity torque encourage asymmetric support structures and can shift the central module off-axis. In microgravity, evenly distributed supports enable centered geometry and mechanical symmetry around the full 360 degree chamber.

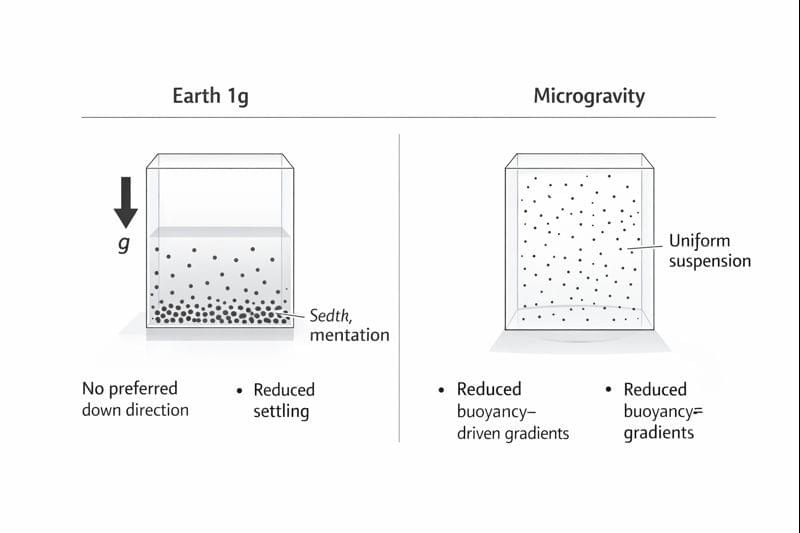

Figure 4. Particle distribution under 1g vs microgravity: in Earth gravity, sedimentation drives a density gradient as particles settle toward the bottom of the container. In microgravity, reduced settling and reduced buoyancy-driven gradients support uniform suspension with no preferred down direction.

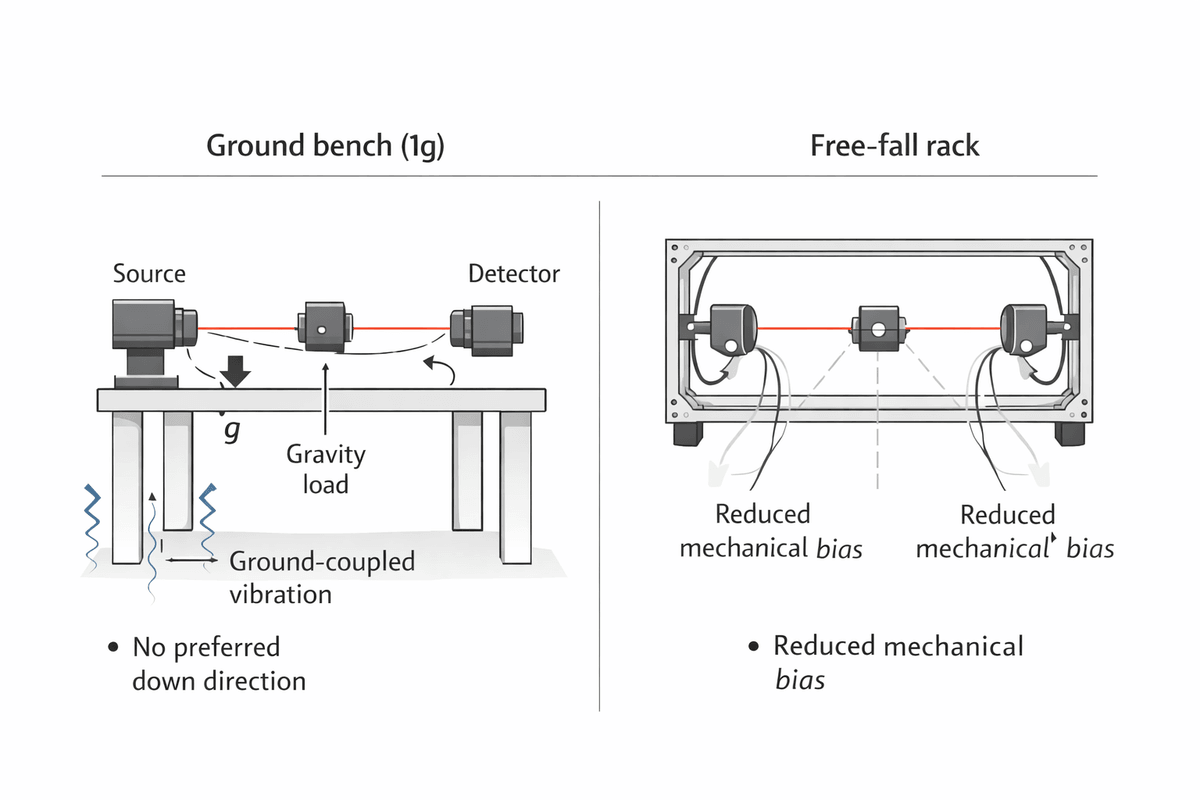

Figure 5. Alignment stability and noise pathways: on a ground bench, floor-coupled vibration and gravity load introduce sag and alignment drift along the measurement path. In a free-fall rack, symmetric mounts and stable geometry reduce mechanical bias and help preserve straight-through alignment from source to detector.